While it is true that most of the time while developing software, we just pick either C++, Java, Python, etc. and start coding simply because A these languages are already well-established and have a lot of libraries and B we are already familiar with them. Yet new languages still emerge from time to time, such as Rust, TypeScript, and Julia, which are happily adopted (and hated) by developers. But few have thought about what are we actually creating.

By computation, you mean…

Computers, by definition, compute. And we utilize programming languages to instruct the computer to compute. However, we actually have no idea what computing means. You may simply argue against this stating that “Well I know Turing Machine!” Indeed, Turing machine is a great computational model. Along with it also comes the $\lambda$-calculus (also my blog post), $\mu$-recursive functions, etc. Surprisingly, these intuitively vastly different models are actually equivalent in terms of computability, which is known as Turing equivalent. We also have created problems that are undecidable and uncomputable. But what makes Turing machine / $\lambda$-calculus special? Why do these (fundamentally identical) computational models decide what is computable? Back to the question, what is computation? It turns out that we have no idea. The Turing-Church Conjecture states that these computational models are identical because they all capture the essence of computation. But what is the essence of computation? It’s never formally defined. (You can’t define it by stating that Turing machine means computation, after all the concept “essence of computation” is there because we have so many coincidentally equivalent models and that may imply some deeper meaning of being computable.) Maybe there exist some other models that have different computational power (in terms of computationability) that we have never thought of. Maybe some problems are computable but not by Turing machine. We simply don’t know.

That’s enough metaphysics nonsense. Why would I care?

The fact is while these models are the same in terms of Math, they still differ in terms of mind and what’s more, performance. Functional guys trying to lure you into their nasty world of $\lambda$-calculus because most of the time functional stuff is more expressive and concise. But you may fight back saying their code going Stack Overflow because of using lazy evaluation wrong is hilarious and absurd. Modern languages no longer base themselves on Turing machine or $\lambda$-calculus but RAM-access machines simply because the model approximates real-world computers. (It would be great if LISP machines still exist.) While it holds that a Turing machine emulates a RAM-access machine, it does so in polynomial time, which is stopping you from coding like this.

But I don’t code using JMP and LOAD/STORE either!

Indeed. Our poor little brains (except theirs) have already been proven to not have the ability to code in assembly, and Haskell isn’t just about $\lambda$-calculus. Abstraction comes into place to free our tiny RAM. By abstraction, I would like to elaborate on it as “working on partial information”. For example, I know that whichever input $f$ always gives the same output if the input is the same simply because $f$ is a function. In the C language, we define functions to hide away actual procedures working solely on the underlying meaning. Good languages free our brains and less-en the information we are working on. It’s abstraction all the way down.

And by creating languages you mean…

Abstractions are great, but (in terms of software engineering) when it comes to abstraction there are no underlying metaphysics implications (thank god) nor formal definitions. It’s about doing whatever the cuss a developer would like to. In Golang you have interfaces, in C you have functions, in C++ you have classes, in Haskell, you have functions all over the place. For the expression problem, some choose to dispatch methods vertically while some do it horizontally. Types are not primitives but abstractions too. Everything is just bits and bytes, interpreting an IEEE double as a short won’t cause any fundamental troubles, and sometimes we do it intentionally. Types present because most of the time we want to keep it consistent. All of these show that abstraction is largely ruled by relativism. That’s where LISP comes into place. It, again I’d like to elaborate as, abstracts abstraction by using macros. Consider the following program:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

(define-syntax unless

(syntax-rules ()

((_ condition body ...)

(if (not condition) (begin body ...)))))

(unless (= x 0)

(display "x is not zero")

(newline))

It defines a macro that expands to

1

2

3

4

(if (not (= x 0))

(begin

(display "x is not zero")

(newline)))

at compile time. One thing that is truly great about LISP macros is that you can do arbitrary computation at compile time. For example, for C++ guys who love classes, there exists CLOS (Common Lisp Object System) that is written in LISP itself, without going into your indeed-turing-complete-but-all-cluttered-together-only-god-can-understand-CPP-templating-nonsense.

Don’t you play tricks on me

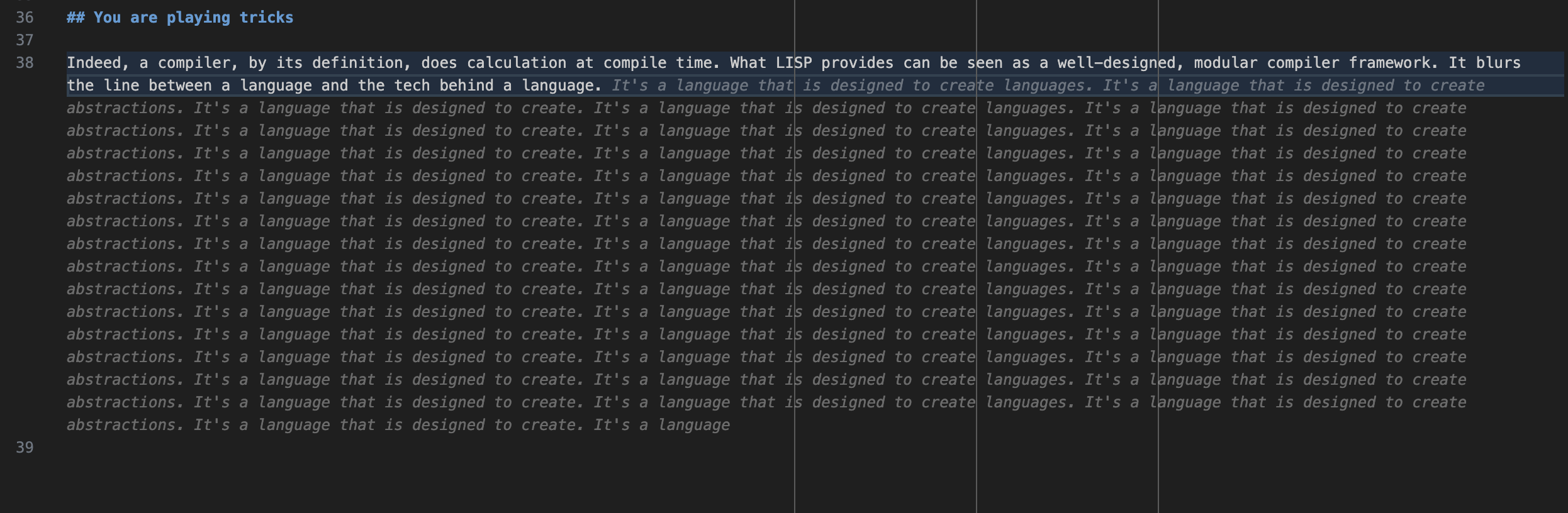

Indeed, a compiler, by its definition, does calculations at compile time. What LISP provides can be seen as a well-designed, modular compiler framework. It blurs the line between a language and the tech behind a language. I think we can happily conclude that by creating languages, we are creating new ways of abstracting data and procedures that fit our needs. PLs will just keep evolving. It’s not a proven fact, it’s some kind of art created by humans.

And it also turns out that even GPT is fond of LISP, so you’d better check it out.