Introduction

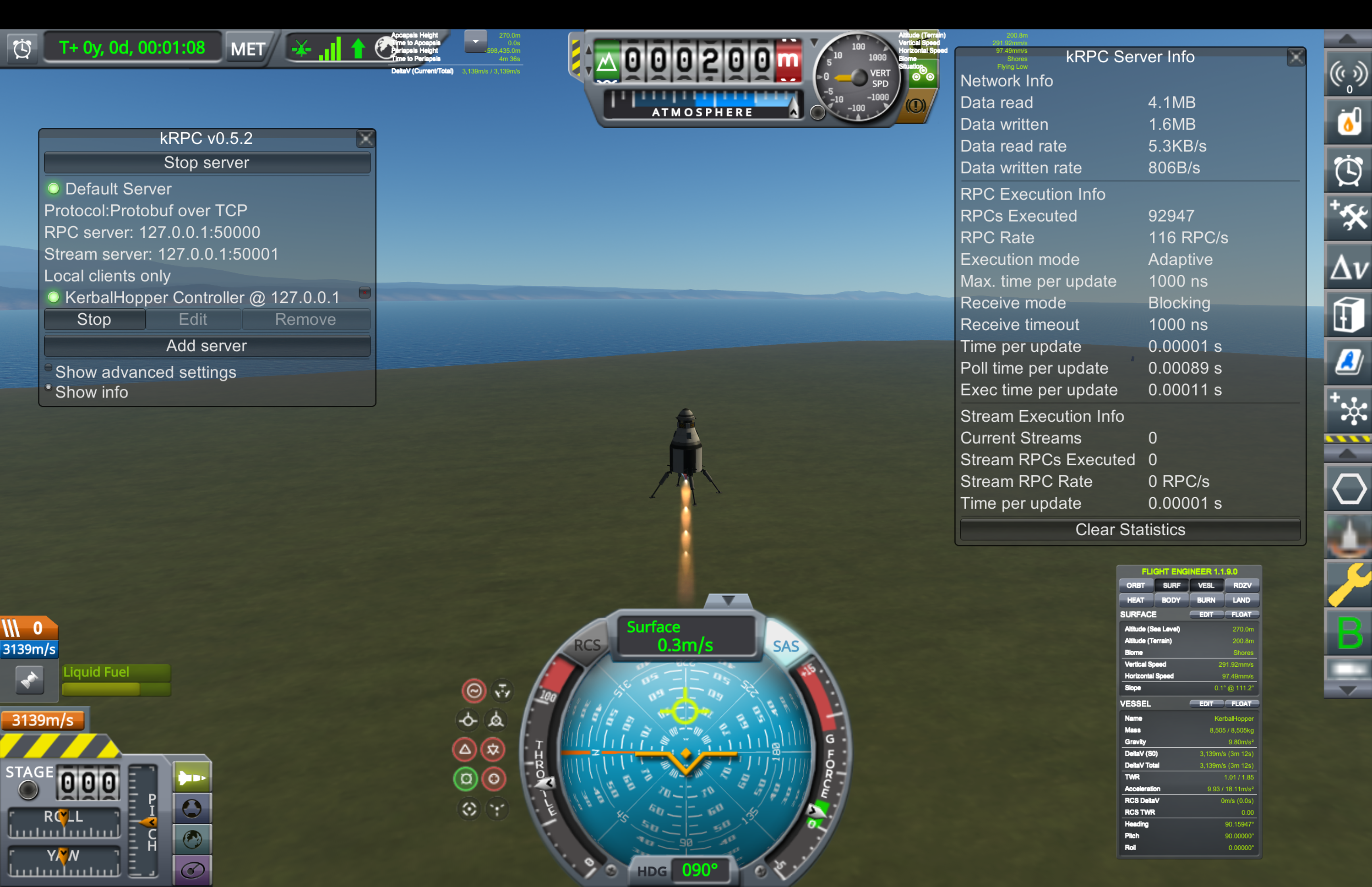

The Starship test flight by SpaceX is incredibly thrilling! True to your old habits, you’ve determined to recreate it in Kerbal Space Program. Perhaps it would be wise to begin by constructing a Starhopper replica. After all, you just need to take off and maintain your altitude for a few seconds, right?

The rocket design is straightforward. All you need to do is affix a Dart engine beneath a Rockomax Fuel Tank, integrate landing legs, a probe core and battery together, and you’re ready to launch.

After fiddling aroud with this craft, you decide to automate this go-to-an-altitude-and-hold-it process. Being a programmer, automation comes naturally to you.

Thanks to the community, a mod called krpc exposes the underlying API of KSP. You can use it to write a script that controls your craft.

The math way

You want to figure this problem out by turing it into an optimization problem. In short, you need to figure out a function $f: \mathbb{R} \mapsto [0,1], \text{time} \mapsto \text{throttle}$. According to Newton’s law:

\[F = ma\]while the corresponding $F$, $m$ and $a$ are:

\[\begin{align*} & F = f(t) + mg + \text{drag}(\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t}) \\ & m = \text{wet mass} - \text{fuel consumption}(\int_{0}^{t} f(u) \mathrm{d}u) \\ & a = \frac{\mathrm{d}^2 x}{\mathrm{d}t^2} \end{align*}\]And you want at some time $t_0$:

\[\begin{align*} & x = h \\ & \frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} = 0 \end{align*}\]Ok it seems that things are getting out of hand. Too many variables are affecting each other. You wonder if there is a better way to do this. And it turns out that this is an engineering question: You don’t have to find an optimal solution, you just need to find a good enough one.

The engineering way

Time to be creative!

P

A pretty straightforward way is to let your throttle be proportional to how far you still need to fly before reaching height $h$.

Let $E = h - x$, then your $f$ can be written into:

\[f = KE\]And you implement this into Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

import krpc, time

HEIGHT = 200

K = 0.01 # Some constant?

DELTA_T = 0.01

class Controller:

def __init__(

self,

target: float,

k: float

) -> None:

self.target = target

self.k = k

def step(self, current: float, dt: float) -> float:

# f = KE

error = self.target - current

return error * self.k

def main():

conn = krpc.connect(name="KerbalHopper Controller")

vessel = conn.space_center.active_vessel

controller = Controller(

target=HEIGHT,

k=K,

)

input("Press enter to launch.")

vessel.control.activate_next_stage()

while True:

flight = vessel.flight()

alt = flight.surface_altitude

throttle = controller.step(

current=alt,

dt=DELTA_T

)

vessel.control.throttle = throttle

print(

"Altitude: {alt} Throttle: {throttle}".format(

alt=alt,

throttle=throttle,

)

)

time.sleep(DELTA_T)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

After a few trials, you find that the craft isn’t going anywhere no matter what $K$ is. Ship keeps oscillating dramatically between $30$ and $230$. This method need some workarounds.

D

Recall what you do when you’re trying to maintain the altitude: When you’re approaching the height, you try not to let the ship fly too fast.

How do you describe not going too fast while approaching? Yes that’s $-\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t} = \frac{\mathrm{d}E}{\mathrm{d}t}$. Again, you take the value, snap a content $K_d$ onto it and hope this works.

\[f = K_p E + K_d \frac{\mathrm{d}E}{\mathrm{d}t}\]And you implement this in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

import krpc, time

HEIGHT = 200

KP = 0.02

KD = 0.008 # Some more constant!

DELTA_T = 0.01

class Controller:

def __init__(self, target: float, kp: float, kd: float) -> None:

self.target = target

self.kp = kp

self.kd = kd

self.last_error = 0

def step(self, current: float, dt: float) -> float:

error = self.target - current

p = error * self.kp

# discrete version of dE

dE = (error - self.last_error) / dt

d = self.kd * dE

self.last_error = error

return p + d

def main():

conn = krpc.connect(name="KerbalHopper Controller")

vessel = conn.space_center.active_vessel

controller = Controller(

target=HEIGHT,

kp=KP,

kd=KD,

)

# ...snip

The method is working! The ship now tends to keep its throttle in an appropriate range. $K_p$ is controlling how fast you want to reach $h$ and $K_d$ is controlling how ease reaching $h$.

However, the ship stuck at somewhere beneath $200$. You pick up a pen and try to figure out where it reaches the balance, that is $\text{thrust}=\text{gravity}$:

\[\begin{align*} f = mg \\ K_p (h-x) + 0 = mg \\ x = -\frac{mg}{K_p} + h \end{align*}\]$h-x = \frac{mg}{K_p}$, which means that the rocket can never reach target height $h$!

I

You have tried to taking $E$ and $E’$ into account however none of them helped. What will you do if you observe your ship is not going to reach $h$? As time goes by you will gradually become impatient and throttle up. How to measure yourself losing patience? Yes that’s $\int E \mathrm{d}t$! As usual, you snap a constant $K_i$ onto it and hope this works.

\[f = K_p E + K_d \frac{\mathrm{d}E}{\mathrm{d}t} + K_i \int^{t}_{0} E \mathrm{d}u\]And you implement this in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

import krpc, time

HEIGHT = 200

KP = 0.02

KI = 0.001

KD = 0.01

DELTA_T = 0.01

class Controller:

def __init__(

self,

target: float,

kp: float,

kd: float,

ki: float

) -> None:

self.target = target

self.kp = kp

self.kd = kd

self.ki = ki

self.last_error = 0

self.integral = 0

def step(self, current: float, dt: float) -> float:

error = self.target - current

p = error * self.kp

dE = (error - self.last_error) / dt

d = self.kd * dE

i = self.ki * self.integral

self.last_error = error

self.integral += error * dt

return p + d + i

def main():

conn = krpc.connect(name="KerbalHopper Controller")

vessel = conn.space_center.active_vessel

controller = Controller(

target=HEIGHT,

kp=KP,

kd=KD,

ki=KI,

)

input("Press enter to launch.")

vessel.control.activate_next_stage()

while True:

flight = vessel.flight()

alt = flight.surface_altitude

throttle = controller.step(current=alt, dt=DELTA_T)

vessel.control.throttle = throttle

print(

"Altitude: {alt} Throttle: {throttle}".format(

alt=alt,

throttle=throttle,

)

)

time.sleep(DELTA_T)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

And there you go! Your hard work has paid off. The ship is now floating at $200$ meters above the ground. You can now sit back and relax until it runs out of fuel!

Conclusion

It’s such a weird method with some nice symmetrical properties. $K_p E$ controls this moment, $K_d \frac{\mathrm{d}E}{\mathrm{d}t}$ predicts the future and $K_i \int E \mathrm{d}t$ reflects the past. You are fascinated by how easy and effective this 28-line of code is - it made no assumptions with the system you are interacting. The same laws still make sense on Duna and Eve. You decide to name it PID, taking the first letter of Proposal, Integral and Derivative.

…and you find out frustratingly that it was invented in 1940s. There’s even a Wikipedia page for it.

Source code of this article can be found here.